Incredible Nature Hot Spots destinations in your neck of the woods.

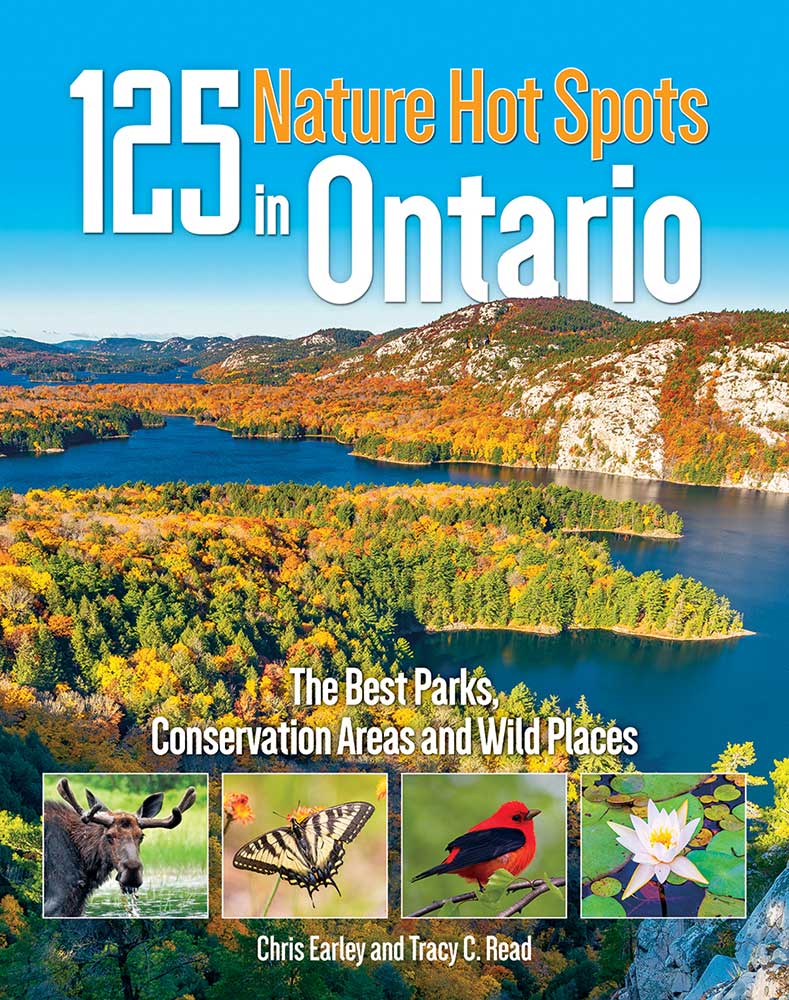

Ontario has no shortage of outdoor destinations to explore which is perfect for anyone planning a staycation this summer. The new book 125 Nature Hot Spots in Ontario: The Best Parks, Conservation Areas and Wild Places by Chris Earley and Tracy C. Read is a lively, informative introduction to some of the province’s best-kept secrets. And for birders, botanists, wildlife lovers, rock hounds and naturalists, it also shares a fresh look at destinations that have made Ontario famous.

The call of the great outdoors is hard to resist. Here are 5 nature hot spots to explore this summer, in various regions of the province, as found in the book:

Northern Ontario: Pukaskwa National Park

This park puts fresh life into the overworked descriptor “pristine wilderness.”

You can reach Ontario’s only wilderness national park by the most conventional of routes. Simply turn off the Trans-Canada onto Hwy 627, which drops you at the Hattie Cove Campground. Once you exit your vehicle and look around, you’ll quickly realize you’ve left civilization far behind.

Pukaskwa National Park sprawls across 1,878 square kilometres of some of the province’s most dynamic landscape. It’s the very definition of “Shield Country.” On its western edge, Pukaskwa hugs the dramatic undulations of the Lake Superior shoreline, where massive headlands push into the waters of Canada’s tempestuous inland sea, creating a dazzling series of deep, sculpted bays. Punctuating the coast are beaches of white sand and water-smoothed stone and stretches strewn with massive pieces of timber tossed ashore by the tumultuous Superior waves.

Inland is a world of rocklined lakes, surging rivers and intact boreal forest that serves as a natural habitat for northern wildlife, such as moose, black bears and wolves. A small, elusive herd of woodland caribou also makes its home here, though the forest industry operating in adjacent lands threatens its territory. The intrepid might consider exploring Pukaskwa by water, but be forewarned: The typically cold and unpredictable Lake Superior waters and winds will inevitably pin down paddlers for days at a time.

For hikers, there are moderate trails that lead to some of the park’s best vantage points. The Beach Trail winds through North, Middle and Horseshoe Beaches; the Southern Headland Trail leads to the lakeside, where, on a late-summer afternoon, you might relax on the sun-warmed granite to the sounds of Superior lapping against the shore. The more ambitious can undertake the 18-kilometre return hike to the White River Suspension Bridge, which soars 23 metres over Chigamiwinigum Falls.

Central Ontario North: Restoule Provincial Park

This provincial park’s low public profile translates into on-the-ground advantages for savvy nature lovers.

Sandwiched between Restoule Lake and Stormy Lake southwest of North Bay, Restoule Provincial Park extends along the shores of the Restoule River. These beautiful waterways serve as an invitation to explore the area by canoe or kayak. Paddle along the base of the towering Stormy Lake Bluffs and look up, way up, for an intimate view of geologic history. In this region, roughly 550 million years ago, a huge parcel of land split and fell away along a fault line, creating a long, steep-walled depression—now filled with the waters of Stormy Lake—that is the southern edge of the Ottawa Valley Rift.

The park offers much to the avid hiker as well the paddler. There are 15 kilometres of trail through a mixed forest of red oak, yellow birch, red maple and sugar maple, but perhaps the most rewarding hike is along the seven-kilometre Fire Tower Trail. This route explores a variety of forested areas, finishing with a spectacular view of Stormy Lake from the 100-metre-tall Stormy Lake Bluffs.

Wildlife watching is an essential part of any visit to Restoule. The two lakes harbour some extremely large snapping turtles as well as river otters, while snakes and turtles live in the park’s wetlands. The area is also home to one of Ontario’s largest herds of white-tailed deer and more than 90 species of birds are found in the park.

Eastern Ontario: Sheffield Conservation Area

A precious piece of the Canadian Shield south of 7

The eastern segment of Ontario’s Hwy 7 runs west to east from Peterborough to Ottawa and famously represents the demarcation between the iconic landscape of the Canadian Shield and the scrubbier farmland south of the well-travelled roadway. A mere 11 kilometres south of 7 on Hwy 41, however, there’s a remarkable exception to this boundary. A short gravel side road leads from the highway to the 467-hectare Sheffield Conservation Area. From the parking lot, you are steps away from a small boat launch and what may be Sheffield’s most beautiful vista.

From the foot of the launch, you’ll be treated to a panoramic view that encompasses a curving shoreline, a marsh shimmering with water lilies and—especially on sunny late-summer afternoons—the vivid blue waters of Little Mellon Lake. Silhouetted against a background of windswept conifers are rounded, rugged granite outcroppings. It is an exquisite microcosm of everything that makes Canadian Shield country memorable.

A loop trail winds some 4.5 kilometres around the conservation area. From the launch, the lower path leads across a grassy stretch to a picnic table, a perfect spot to relax and enjoy the fresh air and the sound of birdsong. With careful supervision, children can walk out on the flat granite rocks for a closer look at the aquatic fauna and small fish swimming in the shallows.

The upper path rises into mixed forest, past granite patches, swamps and glacier-dumped boulders. Both routes are demanding, made tougher by erratic trail markings, and hikers should come prepared with water and snacks as well as orienteering skills. For the less adventurous, a lakeside picnic or a peaceful paddle is an ideal way to appreciate this remarkable area.

Central Ontario South: Thickson’s Woods Nature Reserve

Home to the last old-growth white pines on Lake Ontario’s northern shore, this small woodlot is a sanctuary for migrating birds

The towering white pines at Thickson’s Woods were once officially reserved as ship masts for the Royal Navy, but before the trees were collected, sail-powered naval ships disappeared. With no market for their broad trunks, the white pines stood unbothered for decades, looming over the understorey and providing habitat for wildlife. But in 1983, as developers encroached on the area, the logging rights were sold: It appeared that Thickson’s Woods would stand no more.

In an impressive feat, a small group of concerned naturalists raised the money to buy the property. Although some of the pines had already been felled, others remain today, 150 years in age and exceeding 30 metres in height. These giants define the woodlot, and the gaps led by their fallen brethren have been filled by other tree species, including black cherry, blue beech and mountain maple. In 2001, the naturalists—now working on behalf of the Thickson’s Woods Land Trust—purchased the meadow adjacent to the woodlot, creating the nature reserve we see today.

While the reserve is rich in all varieties of life, it is especially important as a rest stop and fuelling station for migrating birds. The tall pines may act as a landmark, drawing tired migrants in with the promise of refuge. In the spring and fall, the trees come alive with warblers, vireos, fly-catchers and thrushes, while raptors and waterfowl move overhead. Not all birdlife at Thickson’s Woods is temporary, though. Many birds breed here, including forest specialists like the wood thrush and red-eyed vireo. Visitors with keen eyes may even spot resident great horned owls, blending in among the foliage.

Thickson’s Woods is open every day and free of charge. The trails are well established, and the walking is easy. The reserve is not staffed, so be prepared to explore this small woodlot on your own.

Southwestern Ontario: Rock Glen Conservation Area

A hike along a riverbed turns up clues about life on Earth 350 million years ago

It’s not often that human and geological history, physical beauty, biodiversity and family fun come together in one place, but you can find it all at the 27-hectare Rock Glen Conservation Area, just outside the village of Arkona.

Located in the transition zone between the Carolinian Forest Region and the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence Lowlands, Rock Glen is home to an abundance of tree species from each area, from the heat-loving sycamore, sassafras and tulip tree to familiar cold-hardy species such as the sugar maple, beech, white elm and basswood. As many as 50 species of wildflowers burst into bloom each spring, as the sounds of songbirds fill the air and small mammals scurry through the underbrush. If that weren’t enough, there are playgrounds, trails, boardwalks, a scenic lookout and a lovely 10.7-metre waterfall on Rock Glen Creek that cascades into a pool at its base.

But perhaps Rock Glen’s most compelling aspect is tied to what it was some 350 million years ago. In place of a stand of deciduous trees and a rushing river, imagine a shallow sea, teeming with millions of hard-shelled marine animals known as brachiopods, filter-feeding echinoderms named crinoids, horn corals and three-lobed arthropods. As the sea retreated, these creatures were buried in ocean-floor sediment. The result? Layer upon layer of sedimentary rock studded with clues about the Earth’s history, obscured for millennia by a glacier and then a lake. Thanks to an earthquake that split the bedrock 10,000 years ago, these fossils were exposed. Today, Rock Glen is one of the best repositories of Middle Devonian Era fossils in North America, as well as a productive site for artifacts from the Early and Archaic First Nations people who made their living in the area hunting barren ground caribou.

Although you are not allowed to dig for them, heavy rains often free fossils embedded in the walls of the river gorge, washing them down to the streambed. Excited would-be geologists are allowed to take one sample with them when they leave. The whole family can learn more about the area’s human and geological history at the on-site Arkona Lions Museum and Information Centre.

Niagara Region: Woodend Conservation Area

This stand of Carolinian forest offers visitors a sweeping view of the neighbourhood’s biodiversity.

Woodend Conservation Area offers a graphic lesson in the Earth’s history, but be sure to take

a moment to appreciate its human history as well. Originally granted as farmland to United Empire Loyalist Peter Lampman during the American Revolutionary War, this spot saw its share of action during the War of 1812. Perched atop the Niagara Escarpment and located mere miles from military clashes at Queenston Heights, Beaver Dams and Lundy’s Lane, the property proved to be a perfect observation point for armies from both sides. Today, visitors can peaceably enjoy the sweeping views of the escarpment slopes and forests and the meadows below.

This conservation area can be thoroughly explored in under two hours. A trail system allows visitors to hike the escarpment’s base, mid-section and top rim, thanks to a section of Canada’s longest and oldest footpath, the Bruce Trail. As you hike up from the base, take note of the conspicuous rock strata, a literal reminder that you are retracing geological history, step by step. The escarpment creates an invaluable wildlife corridor, and standing at the top, you can watch white-tailed deer graze in the adjacent field. Woodend’s green space enhances the health of the artificial wetlands along its northwest boundary and provides habitat for creatures like the spotted salamander, which marches down the hillside every spring to find water in which to breed.

Note how the surrounding hardwood trees dominate the escarpment slopes. Passerines frequent the layers of this forest, making the area attractive with birdwatchers.

It’s also a popular playground for hikers, cross-country skiers and photographers, while students and educators at nearby elementary schools and Niagara College as well as scientists and nature-loving citizens use the conservation area as a classroom and backyard laboratory. Generations from all walks of life have visited Woodend, burnishing its reputation as a natural treasure.

To find more great nature hot spots in the province, check out 125 Nature Hot Spots in Ontario by Chris Earley & Tracy C. Read.

Buy Book Now